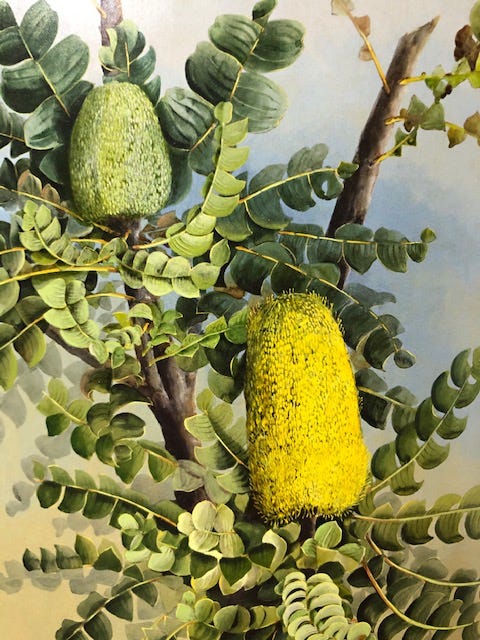

Bull Banksia by Ellis Rowan

Ellis Rowan, ‘the flower hunter’, was a unique artist who thought nothing of bucking conventions in the dogged pursuit of her passion: to record and document as many of Australia’s wildflowers as she could.

She was born in Australia in 1848 to Irish emigrants, John and Marian Ryan, from whom she inherited an artistic talent, a love of nature and a sense of adventure. In an era when it was unusual for women to travel solo, Ellis not only travelled by herself, but as biographer Christine Morton-Evans writes, she

‘traversed remote, inaccessible parts of Australia and New Guinea in search of the rare, the unique and the exotic, relishing the strangeness and often real danger of her surroundings. The sight of this petite, elfin-featured woman, armed with painting gear and parasol, negotiating murky swamps and snake infested jungles in full Victorian attire – whalebone corsets under a high-necked blouse, full petticoats under an ankle-length skirt, high-buttoned boots – amazed all who came across her, and was rarely forgotten.’

Memorial portrait of Ellis Rowan by Sir John Longstaff

During the course of her lifetime, she produced more than 3000 paintings – not only of wildflowers but also of fungi, insects and birds. The National Library of Australia has 970 of her watercolours and is currently featuring a small exhibition of Ellis’ birds of paradise.

In 1916-17 when she was almost seventy years old she travelled to New Guinea to document the region’s Birds of Paradise and wildflowers, and with assistance from Indigenous Papuan people was eventually able to document 42 species. To find these birds she had to go to the settlements Rabaul and Kopopo plus various islands including Sariba Island, New Britain, Ulu Island and New Ireland.

The birds were first captured and brought to her by the natives for she preferred to paint from life, holding them in one hand whilst the other focused on the painting. During this exacting process, she would often sustain numerous pecks and scratches from the frightened bird.

Male and female Princess Stephanie’s Bird of Paradise

According to the exhibit,

‘Some birds were mistakenly brought to her deceased due to miscommunication with her guides. Back in Australia, she sought to paint Birds of Paradise from museum specimens. This may explain why some of her paintings are more vibrant than others.’

She married Captain Frederic Rowan who had fought with the British military in New Zealand’s land wars between the British and the Maori. He encouraged her ambitions and that it meant she would have to leave him for several months at a time so as to journey into wilderness areas to find new specimens. But he would receive long letters from her, rich in description, relating her wonder and awe of the environment around her and some of the challenges she faced, for example, her accounts with deadly snakes. This letter extract is from of one of her first visits to a northern Queensland rainforest.

‘There was such a death-like silence about me that I felt an intruder there, and the thick and tangled mass of rank vegetation completely hid the sun from sight. A few steps farther on I came to an opening, and below me lay a miniature lake, its water covered with large blue lilies floating amid their leaves on which the sun shone through a network of graceful palms. Scarlet, yellow-eyed dragonflies skimmed over its surface while presently a great butterfly tremulously fluttered past, and the sunlight, catching the metallic lustre of its wings, changed them to every rainbow hue … It was a scene of wild, mysterious beauty.’

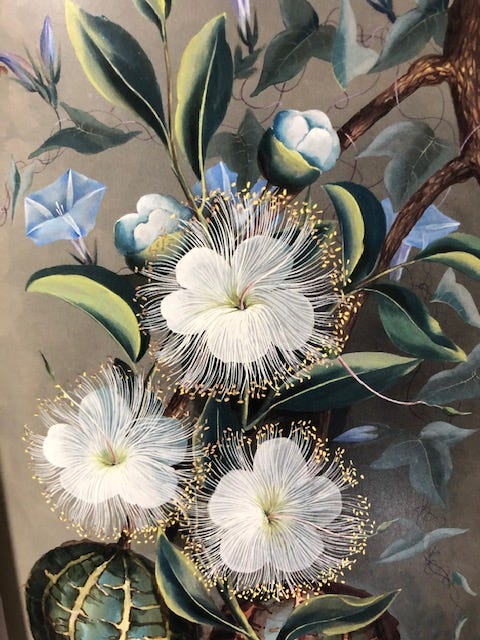

Showy Caper by Ellis Rowan

She traveled with jars of chloroform so that she could capture insects that she would later paint in great detail. Butterflies she couldn’t catch so would paint those primarily from memory. She had a deep empathy for all of the creatures she came across as revealed in this anecdote from Ellis Rowan: A Life in Pictures by Christine Morton-Evans:

‘On one occasion she caught a praying mantis, which she popped into her chloroform jar. Once it was immobilised she pegged the large green insect onto a board, which she then enclosed in an airtight box. When she sat down later to begin painting it, she heard a tiny scraping sound coming from the box; lifting the lid, she saw the mantis was awake and staring at her so pathetically that, she said, her conscience got the better of her and she had to let it go.’

Although always fascinated by botany her impatient nature wasn’t naturally suited to life as an artist when she first tried to master watercolour. She made herself paint for two hours every day ‘but hated it.’ Husband Frederic kept urging her to do better and she did. Interestingly, she avoided formal art lessons ‘in case it interfered with my natural style and eye for colour’, perhaps a wise decision for her art went from strength to strength. She entered numerous competitions and came away with several gold medals but not without some controversy. When she won a gold medal at the 1888 Centennial International Exhibition, this angered the male art establishment, which featured heavyweights like Arthur Streeton, Julian Ashton and Tom Roberts, who protested to the judges for awarding first prize to ‘a mere flower painter.’

Chrysanthemums by Ellis Rowan - First order of Merit and Gold medal, 1888 Centennial International Exhibition

Nevertheless, Ellis Rowan became more committed to becoming a successful, professional artist eventually spending seven years in the United States, painting wildflowers there. What didn’t fare so well in her life was her relations with her only son, Puck, to whom she seemed to pay scant attention. As soon as he was old enough he was sent to boarding school and grew up to be a drifter. Ellis may have regretted her comment, ‘I have never let anything interfere with my work’ when she considered the tragedy of Puck.

He died, quite suddenly at the age of 22, in a South African prison where he was sent after being convicted for forging a cheque.

Motherhood was not really her thing; art, botany, travel and self-promotion were. Ellis became something of a celebrity through her numerous exhibitions and by publishing accounts of her adventures in newspaper and magazine articles, but today she is largely forgotten.

Before her death in 1922 she negotiated with the Australian government to buy her collection of more than 1000 paintings but was not happy with the price they offered. Whilst galleries at that time would sell her work for the equivalent of $1500 a painting, the government would only offer about $300 per picture. The sale was only settled by her inheritors after she died with the result that 970 of her watercolours passed into public ownership under the custodianship of the National Library of Australia in Canberra.

Individual paintings by Ellis Rowan are now highly sought by collectors and have been known to sell for as high as $90,000. She would be pleased.

Giant waterlily by Ellis Rowan

So glad you're written about Ellis Rowan! I really emjoyed her quote from the jungle of Queensland.

Interesting story, beautifully told and illustrated. Thank you for helping restore Ellis Rowan to her rightful place in the history of botanical art!