For watercolourist, Kenneth MacQueen, an artist’s life is full of frequent unexpected riches.

‘All my life, I have experienced thrills of happiness on noting the sweep and colour of a hill, the curve of a wave, the dazzling whiteness of clouds, the shoulder line of a stooping labourer, and the thousand and one arrangements and colour nuances which the eye registers as it surveys the daily scene.’

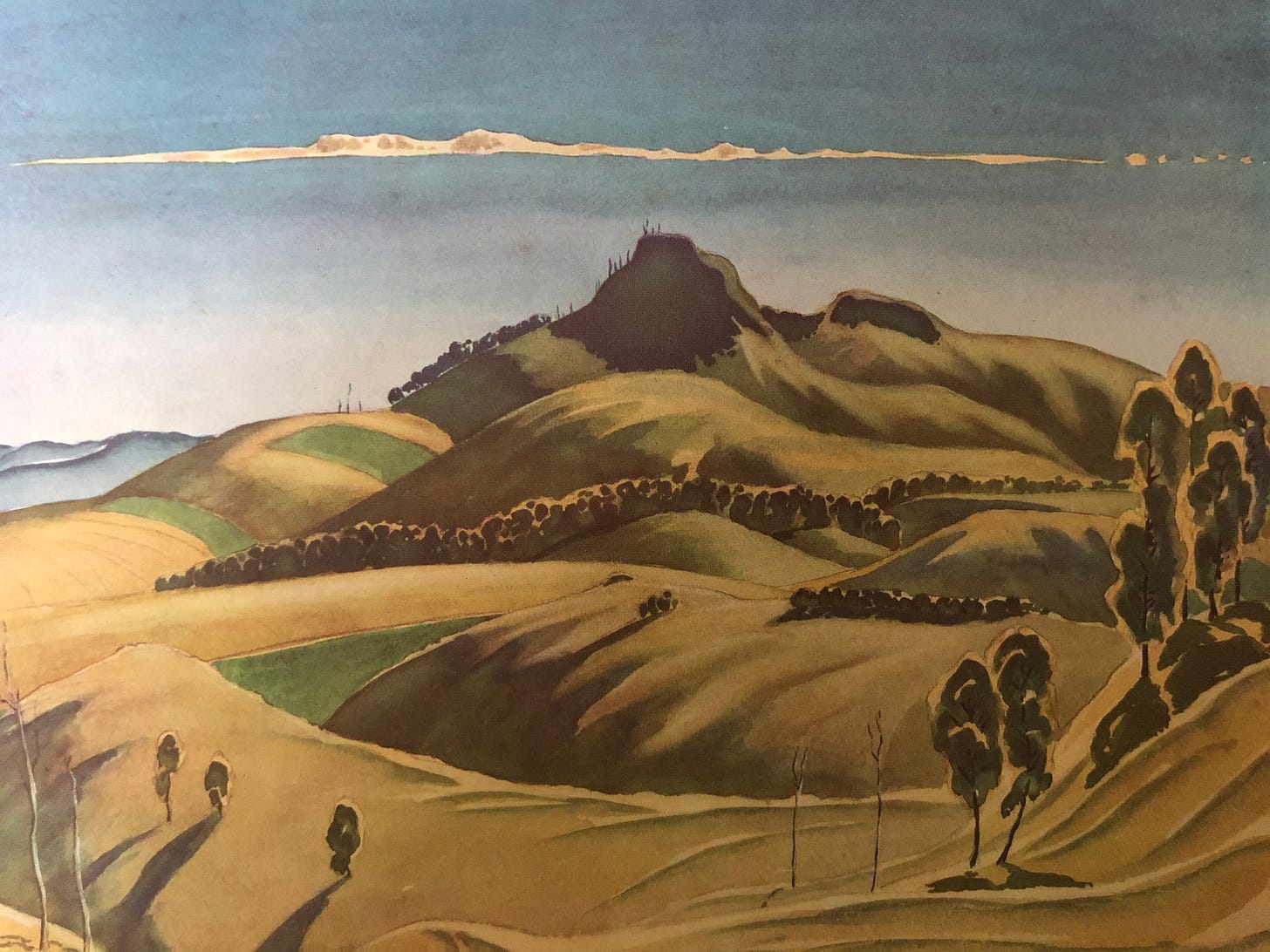

Mt Domville

I’ve long been an admirer of MacQueen’s watercolours, and have become even more smitten now that I am inclined to dabble in the medium myself and know how challenging it can be.

Like many artists, he could not depend on his craft for a living and worked as a farmer on the Darling Downs of Queensland and it was there where he found much of his inspiration.

‘Design in landscape interests me tremendously though involuntarily. When a subject strikes me, and quickens my interest, I find it is nearly always a shape of a tree, hill or cloud that has been the cause.’

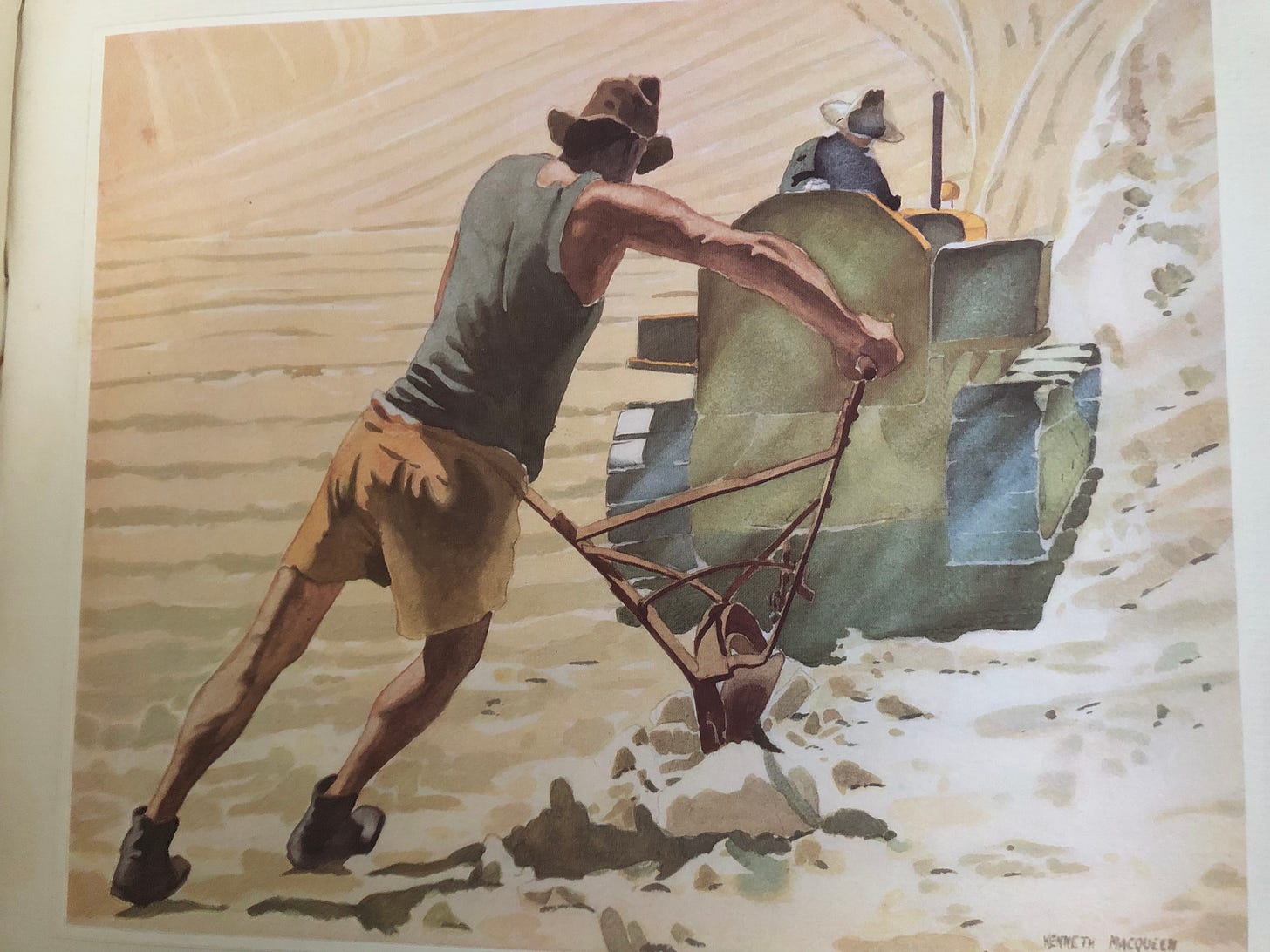

Sinking the Tank

Training his eye to look for large shapes in the sky above or in the landscape around him has influenced my way of looking at the world too and when I go out for a walk, I often try to do the same.

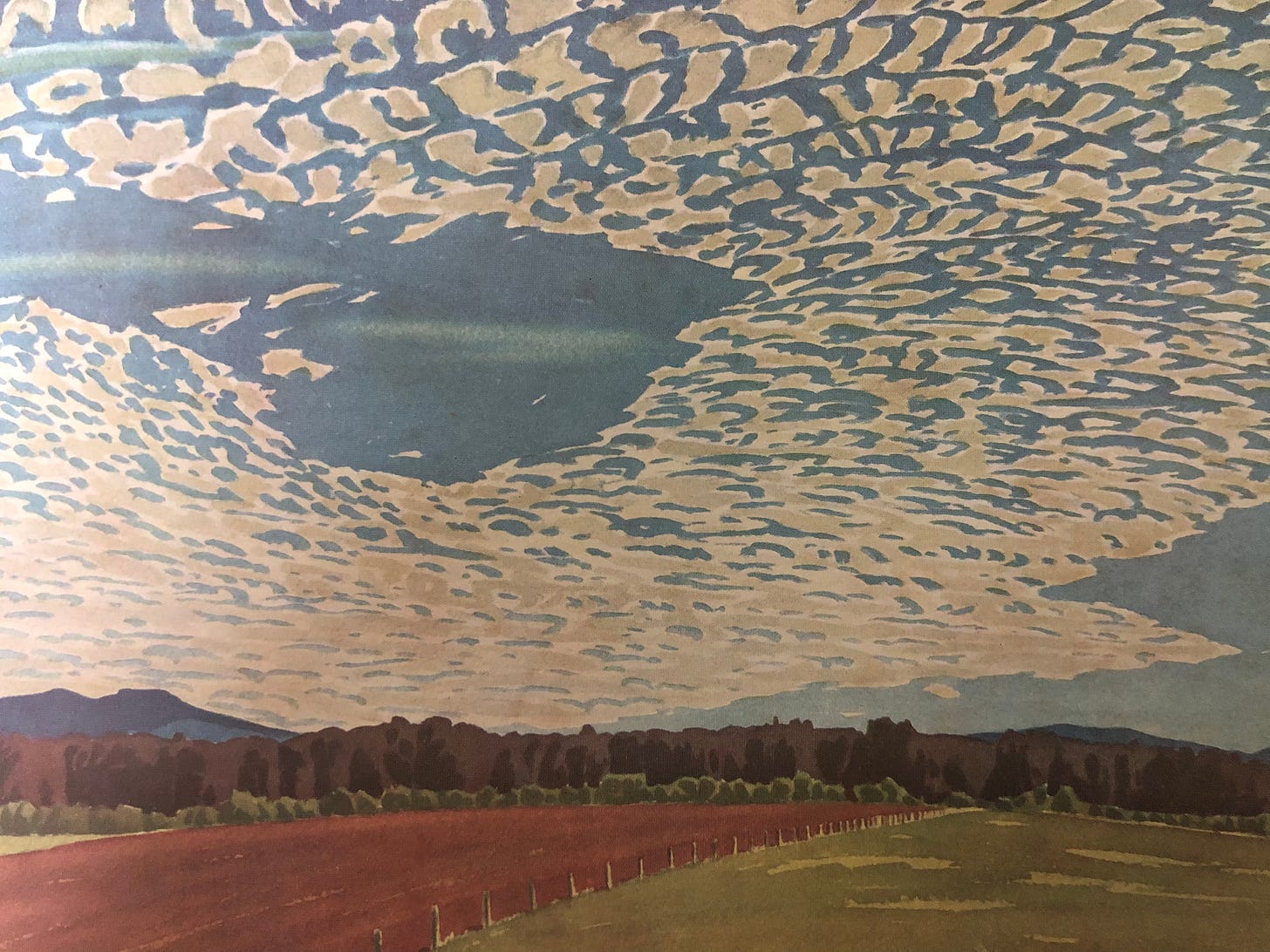

‘Living on top of a mountain, as I do, cloud formations offer a never ending source of interest; very seldom is the sky devoid of cloud patterns sweeping into designs of lively beauty. I rely a great deal on the sky for my compositions. Often the sky is the cause of my painting a subject. A composition of clouds may draw attention to the landscape, and may be so complementary that each apart would not be satisfying, but together the sky and the landscape weld into complete unity of design.’

Mackerel Sky

Not long ago whilst researching the publications of fine art printers, Waite and Bull, I was delighted to find that one of the artists that they had published a book on was Kenneth MacQueen and it is from this work that I have found these images.

MacQueen maintained that in his work he tried to express ‘the joy of living’, such a noble goal for any artist. Yet when I think of his past and the time he spent as a soldier on the Western Front, in battles like Pozieres and Passchendaele with all their horrors, I wonder how he managed to get through that and then return to Australia where he would go out day after day, exploring the beauty around him and creating sublime watercolours.

He said his saving grace in World War I were the writings of Richard Jefferies who claimed to have a mystical communion with nature. MacQueen kept a copy of his work ‘snug in my tunic pocket to give me uplift throughout the misery and discomfort of the mud of France and Flanders.’

He gravitated to watercolour more through necessity than desire.

‘With farming taking up a deal of my time I have drifted from the use of other media to watercolour alone. Maybe watercolour suits me best but mainly because my painting time, which has to be spaced between ploughing bouts or caring for stock, is of necessity scrappy.’

His approach to his work was simple and straight forward.

‘Suppose some interesting shape or sweep of colour arrests me – I will think about it, in all probability for quite a while, and form my plans for attack. Possibly I will do some small pencil notes; planning out the masses and the flow of line.’

And while he did some of his work plein-air, he usually finished his paintings in his studio. The delightful medium of watercolour and all that it can deliver enabled him to work quickly and expressively, moreover it allowed him to preserve a certain freshness that has made his work so sought after by collectors.

He first exhibited in 1927 and went on to have numerous solo exhibitions, mostly in Sydney. In the Australian Dictionary of Biography Stephen Rainbird writes, his ‘Cabbage Gums and Cypress Pines (1940) was purchased for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, in 1941, well before most Australian public galleries began collecting his watercolours.’

That work is similar in subject and composition to this one below, The Red Gum,

The Red Gum

revealing his affinity with Australia’s great gum trees which he wrote had an ‘aura calling for reverence’.

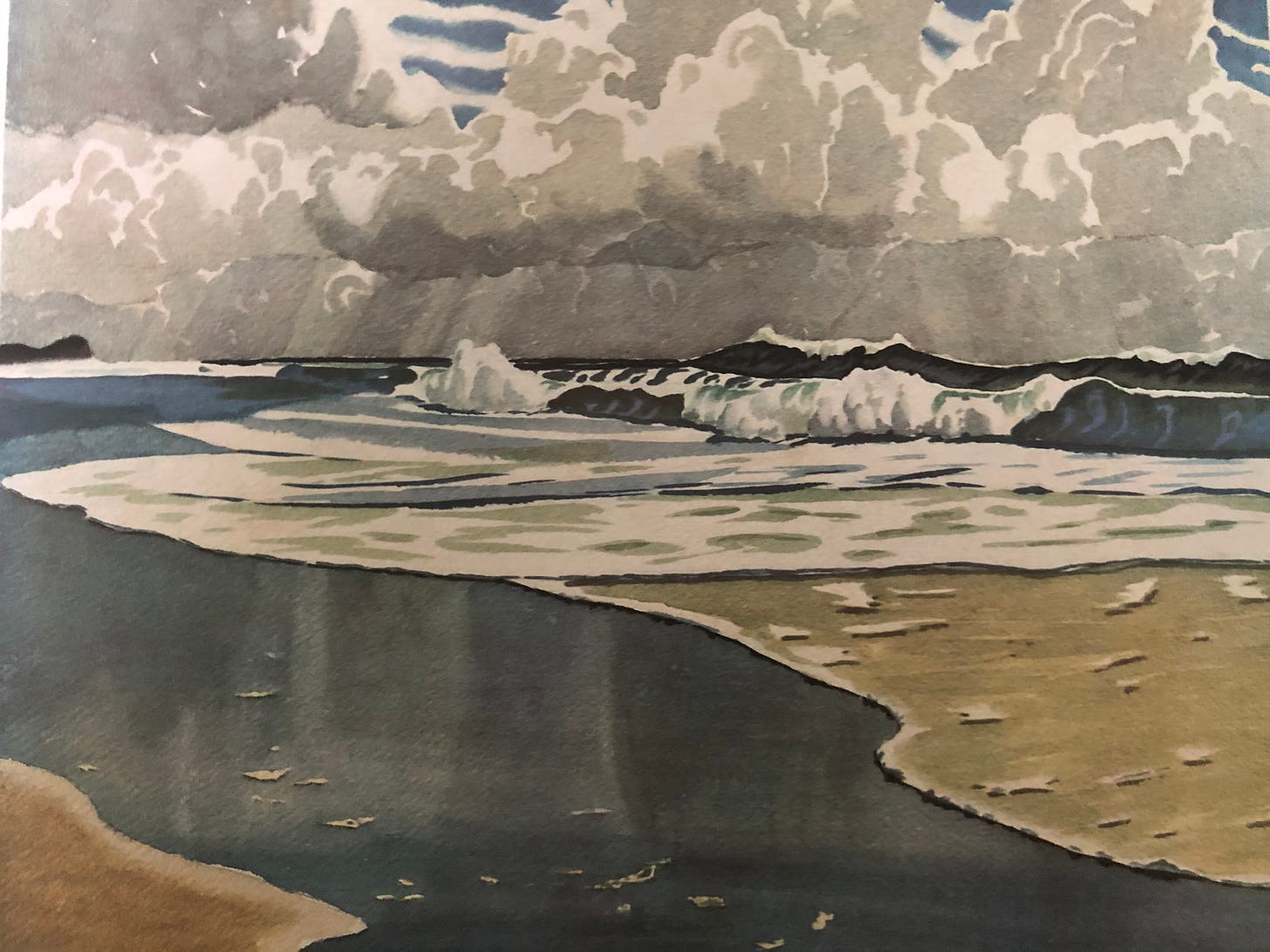

Apart from farmland, trees and skies, MacQueen also loved painting the sea which was about 200 miles from where he lived and worked.

‘The thunder of the surf, the patterned foam and the salty joyous air make one feel the sea must be painted, thought of, read about, and painted again – striving ever to get to the heart of the impulse.’

Coollum Beach

In the art world, although watercolours have long been regarded the poor cousins to oil paintings, MacQueen’s technical ability combined with his strong sense of design, which was in line with early modernist painters, has elevated him to being one of Australia’s greatest watercolourists.

‘Then there can be no greater satisfaction than the feeling as one plods up the hill to the house, the day done, with two or three watercolours in the folio and the suspicion, that in just one of them, you have “got something”.’