Proverbs 16:24: “Pleasing words are a honeycomb, sweet to the taste and healthful to the body.”

Royal National Park, Sydney

Who can forget the sharp, sudden pain of a bee sting? The first I received was when as a five- year-old I fell into a large rosemary bush in full flower and buzzing with bees. Then there were numerous other times over the years when bare-footed I inadvertently walked on bees that were grazing on clover.

I was in awe of my brother who used to like catching bees with his cupped bare hands. He would eventually release them and although he did this repeatedly strangely never got stung. My father would get anxious just watching him and was always trying to warn him of the dangers of running around the garden with a handful of bees. My mother dissented, ‘leave him alone – he’ll be alright’. And he was. She probably knew more about bees than any of us because her father was a beekeeper. But back then she never said a word about that and I only found out decades later when I met a cousin in Latvia who told me how he loved visiting our grandfather and his hives – for all the honey he would be allowed to eat.

Through their painful stings and the rich reward of their sweet honey we grow up with a huge respect for this tiny creature.

Certainly, bees have always been part of our mythology. Every culture has, in some way, deified the bee and its industrious nature. Ancient Mayans saw the bee as the bringer of life and abundance. In Ancient Greece, Zeus, the father of all gods, was reportedly fed by bees as a child. Not surprisingly honey became a key ingredient in rituals around the dead; Plutarch, the Greek historian wrote:

“Mead was used as a libation before the cultivation of the vine and even now those who do not drink wine, have a honey drink.”

With the advent of Christianity, bees played an important role in church rituals. Early Christian sacraments including baptism and communion used milk and honey as part of the blessing. For centuries church candles had to be made from beeswax not tallow for the candles represented Christ.

‘The wick denoted the soul and mortality of Christ, the light the Divine person of the Saviour,’ writes Hilda Ransome.

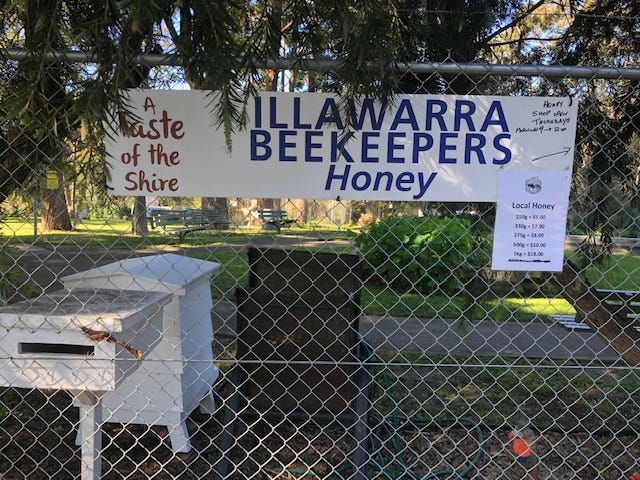

Right now I’m in need of honey so instead of a visit to my local supermarket I thought I would rather pay a visit to my local beekeeper’s club.

The Illawarra Beekeeper’s Association is situated on the edge of the Royal National Park in Sydney’s south - a perfect place for hives as bees don’t like to forage too far from their hives, at most 1.5 km but usually just a few hundred metres.

With only about eight hives at the club, this is not a production exercise to generate funds but there are enough here for education and demonstration purposes. The club boasts more than 380 members, all of whom have backyard beehives, a hobby that’s rapidly growing in popularity. It’s found enthusiasts in all corners of society. The current Governor-General of Australia, His Excellency General David Hurley AC DSC (Retd), is a keen bee keeper known for an ability to corral a swarm back to its hive. Australia’s Federal Parliament now has hives following the example first set by Western Australia’s Parliament which established its own beehives five years ago.

Whilst many primary schools have set up vegetable gardens (my local one even has chickens), Hillston Central Primary School in NSW has invested in ‘flow hives’, an Australian invention that allows for easy collection of honey and also has one side of clear plastic so that the students can see the bees and the honeycomb. The state’s education department has got on board too and is now offering high school students the chance to earn a Certificate III in Beekeeping as part of their high school education.

Ivan, a long-time member of the club, shows me around the club’s hives and tells me about the two hollowed out logs for native stingless bees. There are approximately 1700 different types of native bees but the ones that are efficient at making nectar live up in Australia’s tropical north. The club’s native bees only produce enough honey for themselves and in these cooler climes they need all that honey just to get through the winter months.

A native bee hive (the black, tiny bees well camouflaged)

I know nothing about how European bees first came to Australia and Ivan is keen to give me a little history lesson.

‘You see when the first fleet arrived, the first thing they had to do was work out how to feed themselves.’

The First Fleet had brought seeds for corn and wheat from England and then at a stopover at the Cape of Good Hope, Governor Philip took on board various fruit trees including quince, apple and pear.

‘Well they planted those things and their first crop was quite good but soon after that, they ran into problems. Why? Because the native bees and other pollinators were not interested in pollinating European plants. So, if they were going to establish successful farms and orchards, they realised they would have to get some European bees.’

They came in 1822 on the convict ship called the Isabella which originally left from Cork, Ireland, but stopped in Venice where it picked up the beehives. The voyage took four months and it was the devils work keeping enough alive to last the distance, the ship having to make landfall numerous times so that the bees could revive themselves.

Since then bees and Australian honey have become a valuable industry with approximately 20,000 beekeepers contributing about $99 million to the economy.

There is no doubt that climate change is a posing a significant problem to the apiary industry as are biosecurity threats such as unwanted pests penetrating our borders.

Australia is now at the mercy of longer, hotter summers and with these come more ferocious bushfires. The bees’ foraging pattern is put out of kilter by extreme heat – when the temperature goes higher than 37 degrees Celsius, bees stop foraging for nectar and focus on collecting water to cool their hives. If it gets to more than 47 C degrees the wax hive will melt and be unable to support the weight of the honey which will result in a big mess.

The majority of Australian honey (70%) comes from Australian native flowers and some strains like the popular Manuka honey is reported to have powerful anti-bacterial properties which I can personally vouch for as it’s usually helped the sore throats of my family.

It’s time to leave. I’ve bought my honey and Ivan is busy donning his beekeeper’s suit, ‘I’ve got 200 bees loose in my car … I was moving a hive and thought it was all sealed, but obviously it wasn’t.’

I didn’t ask him how he was going to round up his escaped bees - such are the challenges of an urban beekeeper.

All Photos: LA Hickey

Oh how wonderful your grandfather was a beekeeper! That's fascinating about the native bees and need to get European bees. I loved this article Amanda. I'm going to find the whereabouts of my local beekeeper. Thanks!